Selected Press

Catalogues, Brochures, Magazines, and Online press

2022

Medina, Huascar. “Kansas exhibit unites worlds of artistry and family into a big-hearted whole,” Kansas Reflector, July 23, 2022: Arts and Entertainment, web article (photo).

2022

Hodison, Maya. “Lawrence Arts Center’s ‘Making It Work’ exhibit pairs with Black Lunch Table events, portrays intersection of parenthood and artistry”, The Lawrence Times, July 12, 2022: Arts & Events, web article (photo)

2022

Spencer Museum of Art E/NEWS. Exhibition “Making It Work”, May 29, 2022, Lawrence Arts Center, 940 New Hampshire

Making It Work, on view now at the Lawrence Arts Center, explores the challenges of being a parent, an artist, a caregiver, and a professional during the pandemic. This exhibition brings together six contemporary artists from around the United States whose family bonds and extended communities inform their artistic practices.

Co-sponsored by the Spencer Museum, this exhibition is on view through July 30.

2022

Dan Skinner, Conversations, "Making It Work" Exhibit at Lawrence Arts Center, July 19, 2022, Kansas Public Radio, KPR

2022

Rachel Epp Buller, Renewing The World, July 19, 2022, Podcast.

2022

Maria Vasquez Boyd, ArtSpeak Radio, “Artspeak Radio with Mikal Shapiro, Penny Theime, and Maria Velasco”, May 18, 2022, Kansas City Community Radio, KKFI

2021

Hellman, Rick. “Documentary Explores How Mothers Bring Whole Selves To Art,”, KU News: September 22, 2021, web article (photo), University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS.

2021

AAI ANNOUNCES RECIPIENTS FOR ARTS & HUMANITIES GRANT

Tuesday, May 18, 2021

[…] AAI focuses on enhancing educational opportunity; optimizing the well-being of children, youth, and families, creating accessible assessment systems that better support student learning, especially for struggling learners, and creating educational technologies and data systems that support students, teachers, and organizations.

The two winning proposals strongly align with these areas of focus, through interactive arts programming that deeply engages community and creates dialogue around issues of marginalization and social justice.

Ryan D. Clifford, Assistant Professor of Design and Visual Communication, was awarded for his proposed RadLab! DIY Youth Creative Workshop Series […]

F. María Velasco, Professor of Visual Art, was awarded for her proposed On Our Terms, In Our Own Words project.

2020

“Home-Works. Artist/Mothers in Quarantine”, Zine, Edited by Lauren McLaughlin, Artist and Founder of Spilt Milk gallery, Edinburgh, Scotland, 2020: p. 31 (photo). Order your zine here.

Mothers Are Essential Workers. Home-Works.

“Stay at home to beat the virus”. “Work from home if you can”. “All children must now be home schooled”. “Staying home, works!” These are the messages that have echoed through 2020 as we witnessed a collective return to the home. Home-works zine brings together works produced during the first months of the coronavirus pandemic by 33 artists who are mothers. Located in different parts of the world with varying degrees of ‘stay at home’ orders, and with differing family situations, these artists were united in quarantine. They were united in capturing this unique moment in time, in sharing their personal reflections of this new normal we all face.

For many artist mothers, the lines between home and work were already blurred. For mothers, the kitchen table has long been a site for making art. Stolen moments during children’s nap times, work produced during quiet evenings and creative thoughts appearing while chopping vegetables for dinner. Artists have always looked inwards, reflecting the outside world through the realm of private domestic spaces. Quarantine has given us the time we all craved yet magnified the domestic ambivalence felt by so many. Mother artists have always laid bare the realities of home-working; the joys, the challenges and the inequalities.

As we peer into one another’s living spaces and scrutinise their bookshelves, we have entered a world void of boundaries between public and private personas. In this new world order which has legitimised working from home, will the essential work of mothers finally be recognised? Will the experiences of the mother artist now be more fully understood, appreciated and valued?

In the words of the great Toni Morrison, “This is precisely the time when artists go to work. There is no time for despair, no place for self-pity, no need for silence, no room for fear. We speak, we write, we do language. That is how civilizations heal.”

Lauren McLaughlin, Artist and Founder - Spilt Milk Gallery

2020

”Spaces of Conviviality and The Book of Games”, Catalogue, essay by Susan Earle, Curator of European and American Art, Spencer Museum of Art, University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas 2020: (photo). Download the catalogue on pdf here.

Spaces of Conviviality and The Book of Games

The art of Maria Velasco emerges in connection—to cultural identities, to stories, to carefully chosen materials, to communities—and especially to those who participate in the process of making the work. For Spaces of Conviviality, Velasco engaged local immigrant groups and others living in the Murcia region of Spain, an area in the Southeast near the Mediterranean Sea. A native of Spain herself, but now based in the United States, Velasco inspired residents to participate as part of an Open Studios grant and artist residency hosted by Centro Negra-AADK (Aktuelle Architektur Der Kultur), based in Blanca, Murcia, in summer 2018.

The project derives in part from Velasco’s archival research in Madrid, where she studied several texts including The Book of Games, an illustrated manuscript developed in the 13th century by King Alfonso X “The Wise” (1252-1284). A ruler with broad influence in the Murcia region, King Alfonso X promoted his world view and offered various lessons through the book, using games as a method or platform for interacting with his subjects and audience. Taking this game book as a premise, Velasco invented a card game that participants played. The game created a kind of permission for them to articulate their values and personal identities in meaningful short phrases, using their own words. Volunteers then stitched these phrases onto fabric badges by hand, often working in group sewing sessions, utilizing distinctive shapes and colors for the badges. The final product was a banner or flag of identity badges, installed outdoors on a building in the community. The work is low-tech but high impact. Both the artist’s research, the process, and the flag connect to issues of displacement, and also to histories of hierarchy as well as conviviality. For this and other recent projects by Velasco, the symbolic, emotional, and aesthetic power of visual patterns constitute a key element that provides participants meaningful forms to embody their thoughts. Velasco’s identity flag allowed community members to celebrate their own ideas or traits, instead of those from a past event, or from a privileged ruler from earlier times.

The idea of conviviality arises in various social activities, including those where friends and strangers meet to eat or drink, or to make something together. The idea embraces realms beyond art and focuses on community, as well as self-expression. Being convivial conjures community-building and strengthening our ties to each other in contemporary places of meaning. Its history, though, reminds us of ancient taverns, and to moments such as, for example, 16th-century Iran, when conviviality was employed to consolidate royal power.

What Velasco has masterfully combined is a wise ruler’s 13th-century book of games with historical traditions of conviviality—effectively turning the power dynamics of each one upside down. The “ruled” now create the game, and the spaces of conviviality they gather in serve to democratize authority, rather than stratifying and reinforcing it. The work incorporates Velasco’s research into the powerful use of patterns in Morocco and Islamic Iberia to shape the visual and cultural topography and how they relate to history, identity, social interactions, and societal norms. Part of her project involves participatory opportunities that allow viewers to question their identity in relation to historic memory and to stereotypical perceptions of the “Other.” Velasco’s Spaces of Conviviality helped build a greater understanding of the diverse array of communities in Spain. It called upon the city of Blanca itself and the history of the region as part of the framework. Velasco reveals not only aspects of the local architecture but also deep meanings in patterns that relate to all of us, in different ways, and that connect to our personal and historical identities. The work looks to prior patterns and materials, and also to the present moment. Creating a humble, community-based vision, the project suggests that our best future might result from the hand-made, and from and a highly democratic idea of games paired with conviviality.

Susan Earle, PhD, Curator of European and American art - Spencer Museum of Art, the University of Kansas

2020

Folsom, Alex. “I am Seeking: María Velasco,” College of Liberal Arts and Sciences Blog, February 2020. Watch the episode here or watch it on YouTube down below.

In the College at KU, our research is driven by the passion for improving the world around us. We are explorers, innovators, and dreamers seeking answers to crucial questions in our communities. Learn what professor of visual art Maria Velasco is seeking. The College is a great place to seek the answers to whatever interests you! Visit the College website to learn more about how you can join us and begin your I am Seeking story. For more information, visit the Department of Visual Art at the University of Kansas.

2019

Gieler, Valerie. “Generating The Spark. Research Excellence Initiative Fosters Innovation and Student Growth,” KU Giving Magazine, Fall 2019: p.8 (photo), KU Endowment, University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas. To access the full article on issuu, click here.

Photo credit: Earl Richardson

The Art of Connection.

Generating the Spark: Research Excellence Initiative Fosters Innovation and Student Growth.

A passion for involving the community in her art and inspiration from a 13th century illuminated manuscript took KU visual art professor Maria Velasco to the town of Blanca in Spain’s Murcia region. During her artist residency at Centro Negra-AADK, Velasco created a project influenced by The Book of Gameswritten by King Alfonso X “The Wise,” an important historical ruler in that region. The instructional book has illustrations of men, women and children of different backgrounds playing board games together.

“It’s interesting to see how people navigate this town today, because they keep to their own groups,” Velasco said. “And I thought, maybe we can plant a seed to change that.”

Velasco created a card game with guided questions for people who don’t know each other to sit and talk. “Everyone thought it was strange at first, but they warmed up to the idea,” Velasco said. “They could answer as many or as few as they wanted. The goal is making connections.”

Velasco selected seven questions and some of the answers to transfer onto fabric tiles. The tiles were hand-embroidered by volunteers, and then she constructed an “identity flag” to share the responses. A popular question was: What is a wish for the future? Some of the answers: “I would eliminate borders; have work; peace; I would unlearn.”

REI funding helped Velasco with travel and material expenses and allowed her to bring along Allison Sheldon, a graduate student in textiles who hand-dyed the fabric tiles.

Valerie Gieler, Editor and Communications Team Member - KU Giving Magazine, KU Endowment.

2019

Buteyn Kaylan. 44: Merging Identities - A Panel Of 5 Artist Parent Academics at SECAC 2019. Listen to the podcast here.

2019

Stina Sieg. Parenthood Can Split An Artist From Their Creativity. In Paonia They Can Be Reunited, August 14, 2019. Colorado Public Radio, CO. To listen to the story, click the ‘listen now’ button here.

Parenthood can Split An Artist From Their Creativity. In Paonia, They Can Be Reunited

[…] For the vast majority of artist residencies, a family is almost patently not welcome. The artist is artificially separated from parenthood. But for the first time this summer, Elsewhere [Studios] opened itself up to five artists — mostly mothers — who may not have had access to it otherwise. The Sustainable Arts Foundation, whose mission is to support artists with children, backed the approach with a grant.

For Spanish-born artist Maria Velasco, this residency is a chance to talk about the challenges of being an artist-mother, to hear about resources and tips and just to know she’s not alone.

“People have maneuvered these roles in different ways,” she said. “But it is very inspiring to me to see that you don’t have to give up.”

Velasco, a professor at the University of Kansas, is making a documentary that asks how one can be an artist and a parent at the same time. She’s living one answer. During the residency, she and her 9-year-old son Alex collaborated on a hand-drawn, hand-painted card game. The project, something they came up with together, is a tribute to Elsewhere’s whimsical courtyard, Hobbit-like-buildings and a charismatic cat named Tomatoes. “It really is quite beautiful, to have a sounding board, someone you can create an idea with from scratch,” Velasco said.

As for her son Alex, it was “better than me staying at home,” he said with a grin and a laugh. Velasco has decided she’ll only apply to residencies in the future where she doesn’t “have to choose between my job and my kid and the content of my work and keep all those areas separate because that doesn’t make sense to me.” The ability to bring these aspects of herself together here, at Elsewhere, has been a transformative experience for her — and the other artists in the grant-supported residency.

Stina, Sieg, Reporter - Colorado Public Radio

2019

Open Studios, María Velasco, Marble House Project, Dorset, VT. To listen to the presentation, click here.

2017

“Artists Inhabit the Museum. A Decade of Commissions and Artist-in-Residence Projects”, Catalogue, edited by Kris Imants Ercums, Curator of Global Contemporary and Asian Art, Spencer Museum of Art, University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas, 2017: pp. 20-25 (photo)

Stop Look Listen was one of many initiatives through which the Museum sought to reconceptualize interaction with its collection, and anticipate interaction outside the Museum, in this case the parking lot. It required viewers to move through the Spencer, inside and out, in order to gain a new perspective on the collection as well as on ways that artists might reconsider or reimagine those objects. This drive to extend the museum experience beyond the confines of its building anticipated the literal opening of the architecture that occurred during a 2016 major renovation. Large chunks of the original 1977 limestone exterior walls were replaced with expansive windows, allowing a direct dialogue between inside and out Davidson-Hues and Velasco's intervention at the Museum without physically moving any of its artworks functioned in a way analogous to hypertext, allowing for alternative pathways and additional or related information within a text without disturbing its original syntax. In Stop Look Listen’s allusion to traditional signage of travel and tourism, it undercuts existing hierarchies hidden within it. Now, 10 years later, Stop Look Listen has inspired the creation of additional audio content that is delivered through the Museum’s mobile app.

Kris Imants Ercums, Curator of Global Contemporary and Asian Art, Spencer Museum of Art.

Innocence & Menace: María Velasco at Living Arts

Began as illustrations for her brother’s 2011 published book of poetry, Maria Velasco’s A Very Long Night explores the enigmatic and intersecting landscapes of play and fear. After the initial collaboration, Velasco remained intrigued by recurring characters and sought to expand the narrative to include movement in space and time. What has resulted is a site-specific layering of hand-drawn images and video which capture the spirited world of children and the menacing way adults can threaten that environment.

An Associate Professor of Art at the University of Kansas, Velasco’s installation presents a non-linear storyline in which the specter of child abuse is at once present and absent. An adult perpetrator roams her graphite drawings, disrupting the whimsical scenes of play between two children. The outcome of this interaction, however, is far from clear. Rather, the viewer must investigate the variety of roles played throughout the story to draw their own conclusions. “It is a work with many levels,” Velasco notes. “How those levels work against each other creates, at first, a sense of naïveté and fun but also the sense that something is not quite right.” Though viewers may enter the work via the children’s drawings, Velasco hopes they will stay to see that there is darkness within the work as well. As in the two previous exhibitions of A Very Long Night (in Argentina and Kansas), Velasco makes the work anew in her presentation at Living Arts. “It is an intense installation which involves the drawing of a full-size home, complete with a kitchen, bathtub, and living room, in graphite directly onto the walls,” she stated. These domestic scenes serve as the background for her use of large-scale digital prints of figures and silhouettes. Adjacent to these tableaus is projected the animation of child-like drawings which Velasco continues to develop as the project evolves in each subsequent installation. Her desire to present A Very Long Night at Living Arts is an effort to continually push the project. In this way, each exhibition of the work serves as a rite of passage for Velasco as she aims to present material that, though not autobiographical, embodies her direct presence.

She has also expanded the project by participating with counselors and psychologists in a workshop for aspiring therapists. The goal of the workshop was for attendees to develop confidence in utilizing tools, such as the intermingling of text and drawings, as a way to open lines of communication with and avenues of expression for their patients. Though Velasco feels that she is not qualified to work directly with survivors of abuse, she ultimately aimed at helping those who have experienced such trauma.

The experience of developing the workshop, combined with her own research, has allowed Velasco to create levels of tension in her layering of drawings, prints, and video. Her intensive installation process produces a quirky yet sinister landscape. Viewers navigate this terrain and its disturbing narrative, the conclusion of which ultimately rests in their hands. Velasco’s expansive installation embodies all of the whimsy of a child’s world including the monsters, real and perceived, that lie within.

Mary Kathryn Moeller, M.A, Contributing Writer, Art Focus - Oklahoma Visual Arts Coalition.

2012

Candiani, Alicia. "Proyecto Ace. Una Afortunada Coincidencia de Manos e Ideas" Gran Angular, Grábado y Edición Magazine, Diciembre 2012: Numero 36, pp. 32-40 (photo p. 36)

Alicia Candiani, Artist.

2012

"The Lighton International Artists Exchange Program. LIAEP Recipients 2008-2012," Brochure, (photo)

2012

"La Noche Más Larga/A Very Long Night", Exhibition Postcard, Proyecto 'Ace, May-June, 2012: (photo)

2011

"Professor Profile", The Viewer As The Artist, KU Oread Magazine Online, 2011

The Viewer As The Artist

Professor Profile, The Viewer As The Artist, María Velasco, Visual Art

As far as Maria Velasco is concerned, viewers should not just stand back and passively view a piece of art, they should be part of it. Velasco, Associate Professor of Visual Art, teaches and practices installation art. In a new KU YouTube video, Velasco discusses installation art, what it is and how it differs from other mediums, her work, involving an audience in art, teaching and what viewers can take from an art installation.

Installation art is a word that doesn't usually carry a specific image with it, Velasco said. It is an arrangement of various objects, utilizing different mediums. Then they're put together in such a way that there is a set of relationships between them.

In her work, Velasco is more concerned with spatial relations and the audience than a particular medium. She has done installations on KU's campus, throughout the country and in several locales in South America. The works often explore themes of individual and collective identities and their relationships to female sexuality and language. The audience is often just as big of a part of the installation as the creator. One of her works composed a poem, spelled out in edible chocolate. As people viewed it, slowly they realized that it was acceptable to, literally, eat the art. In another piece, viewers do a lasting contribution to the project and took something away. The piece rotated around the idea of hopes and dreams and wish making, Velasco said of her work That Which Holds Promise... So I created a series of stations or opportunities in the gallery space for people to make a wish and contribute, materially, something to the piece. We had a pile of clay in one area and asked people to take a piece of clay, compress it and make a wish and add it to a wishing well that was set up in the space.

Her students tend to be those that are looking to work in multiple disciplines. They often have experience in various mediums and are looking to bring them together in an installation. The students annually display their work in a public exhibition. The display gives them an opportunity to show their work, and to learn more about two sides of the art world. The annual installation show gives the students the opportunity to see themselves in a professional setting, Velasco said... It gives them a view of the practice of art, versus the making of the art.

Whether an installation is one she produced or came from the mind of her students, Velasco said she hopes viewers take something away from the exhibition, and that the artist learns from the viewer. When a viewer comes to see an installation, I hope that they will have an experience that will transform them, or touch them in some way, she said. I would hope that they would make a personal connection.

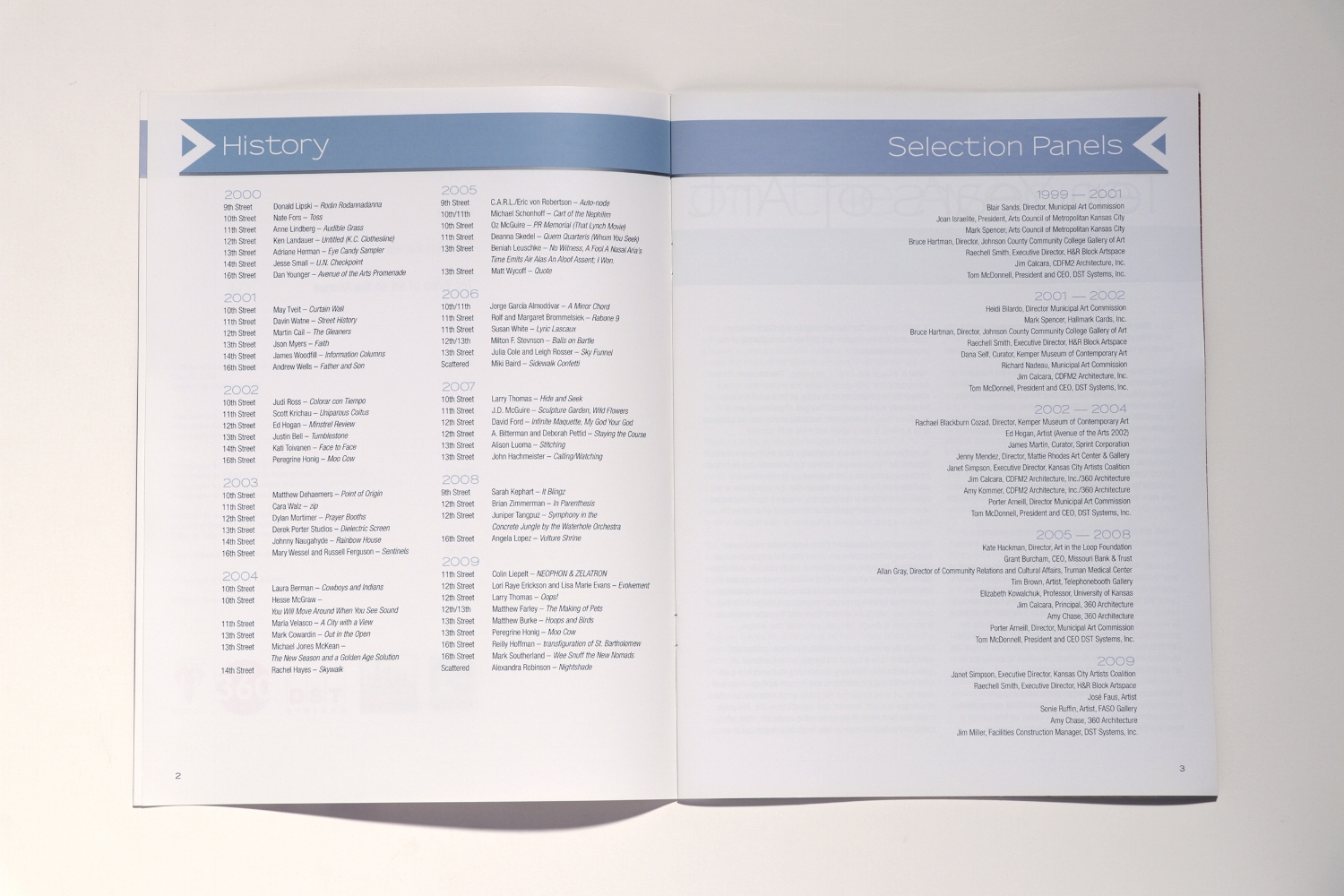

2009

"Avenue of the Arts Celebrating Ten Years", Catalogue, edited by Tracy Abeln, Janell Meador, and Sonya Baughman, Review Incorporated, Kansas City, Missouri, May 21, 2009: p. 17 (photo). Download the catalogue on pdf here.

Velasco created a faux 'tourist viewer' (the kind you put a quarter into to get a binocular view of a scenic overlook), which was positioned on the sidewalk at 11th and Central facing east. Viewers who peered into the contraption thought they saw the real scene but were surprised with some unexpected visions. The artist used a videotape of the actual view, then added some of her own imagery: people skateboarding up a building or peering out of a window or just appearing and disappearing.

Tracy Abeln, Janell Meador, and Sonya Baughman, Editors, Review Incorporated Magazine.

2009

"Publications, Artists Commissions, & Other Projects", Register, Spencer Museum of Art, Volume VII, No. 10, July 1, 2007-June 30, 2008: p. 108-109 (photo)

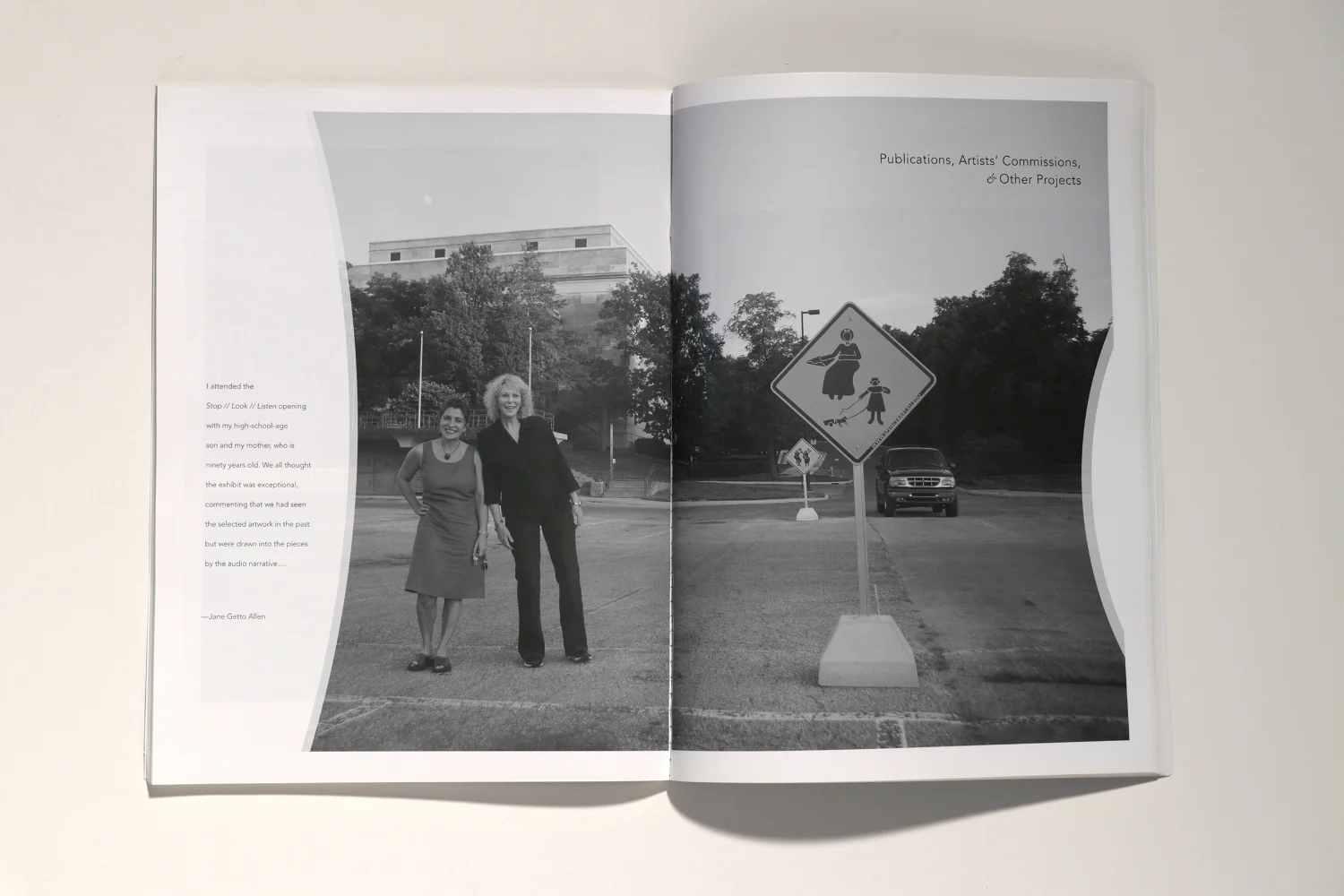

I attended the Stop // Look // Listen opening with my high-school-age son and my mother, who is ninety years old. We all thought the exhibit was exceptional. commenting that we had seen the selected artwork in the past but were drawn into the pieces by the audio narrative...

Jane Getto Allen, Spencer Museum of Art Visitor.

2008

"Stop Look Listen Extended Through Spring", Spencer Museum of Art, vol. XXXI, no. 3, March-April-May Calendar, 2008: p. 19 (photo)

By popular acclaim, the Spencer is extending this special-commissioned installation--a combination of indoor/outdoor signage and MP3 audio tours by artists María Velasco and Janet Davidson-Hues. Inspired by images firm the SMA collection and common traffic signage, their works outside the museum announce "Warning: Art Approaching," while MP3 audio tours inside offer offbeat looks at the collection.

2008

"In Residence: Recent Projects from Sculpture Space", curated by Christa Erickson and Patterson Sims. Elizabeth Foundation for the Arts, New York, NY. Download the full press release on pdf here.

Where else can you sink your teeth into frosting covered poetry, peek into hanging microcosms, observe nature work against itself, and witness sound waves transform into rippling light?

From September 6 through October 18, 2008, EFA Project Space invites you to IN RESIDENCE: Recent Projects from Sculpture Space, an exhibition celebrating the cultivation of the creative process and the crucial contribution organizations such as Sculpture Space (Utica, NY) provide to artists. Curated by Christa Erickson and Patterson Sims, this exhibition provides a sampling of work by artists who have recently participated in Sculpture Space’s residency program.

At the opening reception Maria Velasco will be performing her evolving project Isn’t It You, as she serves up edible poetry on trays. Velasco invites public interaction (through ingestion), but also neighborhood involvement, as the ornate script lettering will be cast cupcakes baked and decorated in collaboration with Hell’s Kitchen’s Cupcake Café. A permanent element of the artist’s interactive performance will remain on display throughout the show. Hanging from pulleys across the way are Carlos Ferguson’s Suspended Worlds, simply colored boxes that may be lowered and raised to eye level allowing the viewer to peer through the peepholes, revealing colossal spectacles in dioramic proportions. Pushing scale in the opposite direction is Wennie Huang’s Red Sprawl, a bold, red, twenty-four foot wide wall-bound tree created by twisting together what the artist describes as “5,000 chenille stems”, a nostalgic material at a closer look. Memory serves as inspiration in Takafumi Ide’s Reverberate, an ethereal work where inaudible sound waves are filtered through lit drops of water into halos of light undulating across the wall. Nearby is David Bowen’s 4phototropic devices, a light sensitive device consisting of 4 four leaves attached to photo-resistors and motors, constantly reconfigure themselves as they attempt to expose themselves to light. This play on nature and mortality juxtaposed with artficial technology also occurs in David McQueen’s Quaking Aspen/Nervous Empire, described by the artist as a “colony of 80 …Aspen trees stemming from a shared root system and drawing power from a single elaborate power source… which sends pulses of electricity through the roots,” causing the trees to quiver and tremble.

What unifies the exhibition is the very singular vision of each artist that, when given the opportunity of space, time and resources, results in something uniquely articulated, as if it has materialized from a parallel dimension: from Jae-Hi Ahn’s, glistening gem-like hanging vines; to Hairpiece, a dizzying installation of wound synthetic hair by Las Hermanas Iglesias; to Beth Krebs’ magically spare illusionary room; to Abe Ferraro’s Climbing Machine video documentation of an elaborate construct which generates drawings as the artist climbs; to Jina Valentine’s meticulous and destructive transformation of herbal remedy boxes; and finally, to Sterz’s strange, unearthly floating object mirrored in an acrylic puddle on the floor.

By partnering with Sculpture Space on this exhibition, EFA Project Space begins to fulfill its goal to provide a unique space for collaboration with other art and cultural organizations, thus expanding audiences for the arts while bridging gaps in the art community [...]

“Residencies at Sculpture Space are a rare luxury for artists to focus exclusively on their work with support. The shop environment that originally characterized Sculpture Space’s origin has expanded, allowing for the pursuit of the broad array of practices associated with sculpture today. The expansion of practices also incorporates the notion of site - in this case the post-industrial small-scale urban landscape of Utica, NY. This featured selection of works further characterizes ‘sculpture’ as a sensitivity to and facility with a diversity of materials - craft and food items to electronics and light to those more traditionally employed. Selected artists demonstrate great ingenuity in finding, fabricating, and transforming materials into imaginative works, many of which reflect on timely issues..”

Christa Erickson, Co-Curator and Sculpture Space Artist-in-Residence, 2007

“Vibrant and fluid, the work created by this small selection of the large array of sculptors who have passed in recent years through Sculpture Space attests to the freedom and unfettered creativity that clearly flowers there. These works also strongly confirm how broad the category of contemporary sculpture is and how many superior talents exist who are still less known and seen than they should be. The Elizabeth Foundation for the Arts is to be celebrated - along with these artists - for bringing an increasingly esteemed Utica, New York artists’ resource to Manhattan and forcefully reminding us that potent art is made in the State’s smaller cities too.”

Patterson Sims, Co-Curator. [...]

2007

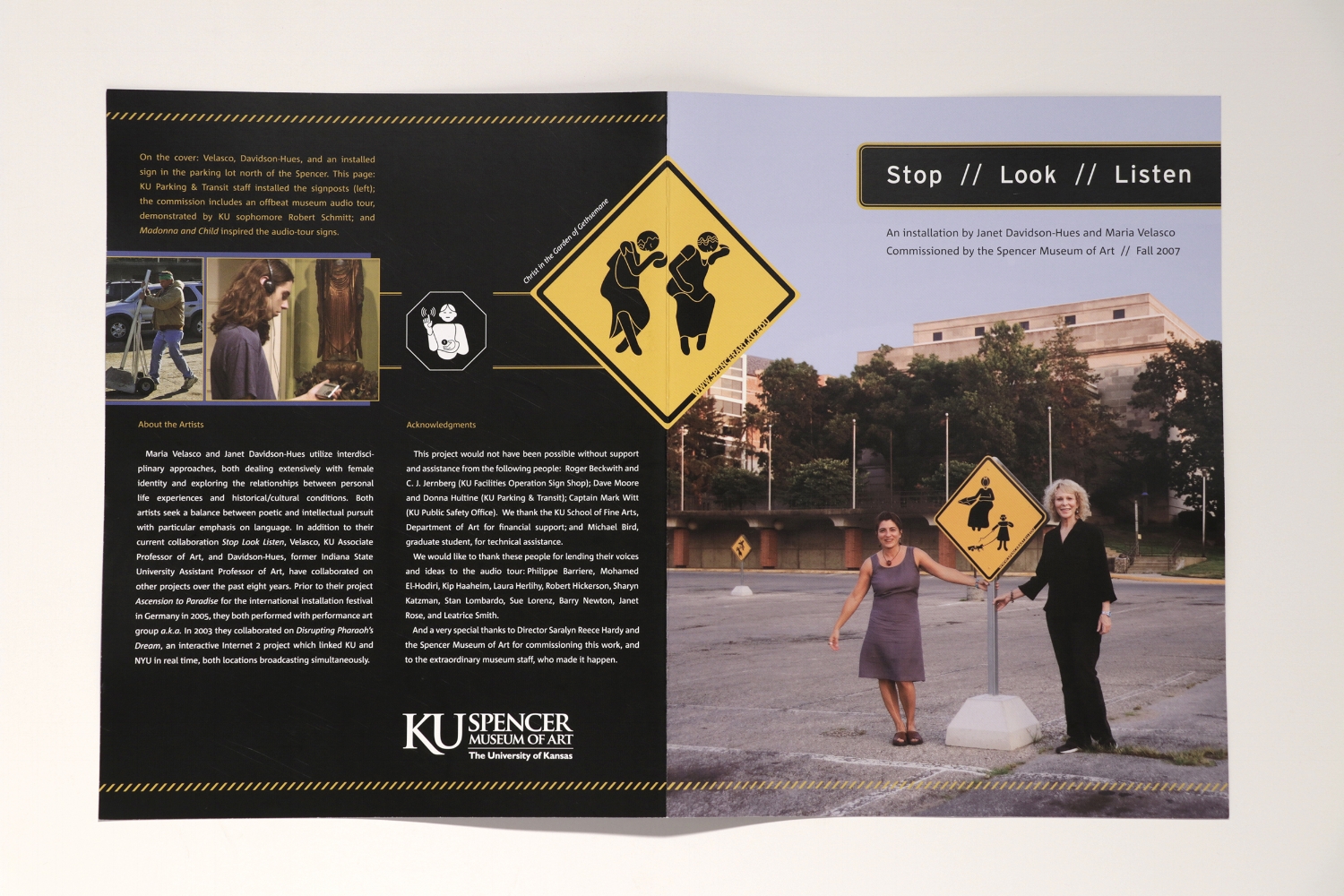

"Stop Look Listen", Exhibition Catalogue, essay by Susan Earle, Curator of European and American Art, Spencer Museum of Art, University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas 2007: (photo). Download the catalogue on pdf here.

Stop Look Listen

Artists Janet Davidson-Hues and Maria Velasco have created a complex intervention into the Spencer Museum of Art that they call “a way-finding system.” Through signage that they have placed outside and within the museum, and an audio tour of the museum’s permanent collection, they seek to intervene in the museum-going experience, encouraging visitors in our hyper-stimulated, media-rich world to slow down and, as the work’s title says, stop, look, and listen.

The system begins outside, with seven signs placed around the museum; their diamond shapes and bright yellow colors mimic the look of roadside warning markers. Imprinted on them are black silhouettes derived from figures that appear in the museum collection. These figures are transformed to look like the stylized icons of international signage, found worldwide along highways and in airports, and designed for intelligibility. A multi-figural baptism scene from the sixteenth century, for example, is reduced to a streamlined, single figure with a floating head receiving drops of water. In these signs historical images are reincarnated and speak to us in an elemental way, defying the ordinary and perhaps saying: “Warning: Art Approaching.” In their accessibility and openness, the signs interrogate the power of images and art in our society, and they humorously disrupt our expectations. The system continues inside the museum with a self-guided audio tour keyed to a diverse set of objects in the museum’s permanent collection. Davidson-Hues and Velasco have designated each object along the tour with a stop-sign-shaped label featuring an image of the infant Jesus, again transformed into the iconic style of international signage. Part technological and part curatorial, the system comments on other works of art, reinterpreting earlier objects to bring the past into the present using unconventional and post-modern methods and materials: traffic signage and MP3 players. The choice of MP3 technology reflects the project’s accessibility: by using generic MP3 players, the artists encroach upon territory that until recently was the exclusive domain of Acoustiguide and other systems that accompany blockbuster exhibitions. The artists encourage us to re-think the authoritative texts on those soundtracks, and to instead embrace a more personal, thoughtful experience.

As we listen to the audio in front of each tour object, we are immediately transported. There are layered sounds and words, potent yet elusive, mischievous, unfolding in our heads, in terrains unexpected. The variety of resonant voices and texts—some sensual, some challenging, some almost mesmeric—suggest the openness of each object (and the artists) to multiple perspectives and varied meanings. The two-voice audio track for Carol Haerer’s painting Abiquiu, for example, includes excerpts from Haerer’s letters while also urging us to move to different viewing positions as we listen. The track for Mimi Smith’s Steel Wool Peignoir argues for the work’s significance as an early feminist icon, commenting on how it both attracts and repels us. The track for Standing Amida Buddha evokes a meditative state, incorporating a chant written by monks specifically for this Buddha.

Perhaps the most powerful audio is the one for Lesley Dill’s Thread Man (1992). Using beautiful binaural sound technology, it mimics the poetic quality of Dill’s sculpture and the voice in our own heads, fiercely cutting to the core of how fragile language can be, in contrast to the tangibility of voice, and skin. The audio voice calls the sculpture “a textual mummy… / A jumble of words dangling” while also posing provocative questions, such as “Is there an obligation to speak?” and “Is decoding the wire words like picking bug droppings out of pepper? / What are words for, when no one listens first century art, and is one of various laboratories through which the museum has sought to reconceptualize interac-anymore?” The work intones a reminder that art, like life, is about experience and subjectivity, not just about objects.

Stop Look Listen was commissioned by the Spencer upon the reinstallation of its galleries of twentieth- and twenty first century art and is one of various laboratories through which the museum has sought to reconceptualize interaction with the collection. The lab idea helped to inspire the experimental, playful qualities of the artists’ work. Velasco and Davidson-Hues are no strangers to experimentation, performance, or public art, having collaborated a number of times, most recently as participants in an International Installation Festival, Vogelfrei 6, in Darmstadt, Germany, for which they created Step-by-Step Ascension to Paradise, a work installed in a garden that reinterprets the story of the temptation and fall of Adam and Eve and connects to this project at the Spencer Museum of Art by being similarly based on historical iconic figures.

Susan Earle, Curator of European and American Art, Spencer Museum of Art.

2007

"Dialogue with the Director", Spencer Museum of Art, vol. XXX, no. 4, March-April-May Calendar, 2007: p. 4 (photo). Download the article on pdf here.

Dialogue with the Director

March/April/May 2007

In celebration of the spring opening of the Spencer’s renovated 20/21 Gallery, the museum has commissioned a project from Lawrence artists Janet Davidson-Hues and Maria Velasco. As a way to engage visitors as active observers, Davidson-Hues and Velasco have created a wayfinding system based on signage that not only will guide and inform, but also challenge, surprise, and interrupt. The project, titled Stop Look Listen, will have external and internal components, including various types of signage and iconography, as well as a self-guided audio tour composed of mischievous, insightful, or ambiguous comments, unanticipated words and sounds. By creating a playful wayfinding system both inside and out, and providing an unpredictable audio tour, the artists intend to create a system for people to move through a space that feels unique. Chance encounters with familiar signs, symbols and sounds will provide viewers with an enhanced museum experience. Ideally, viewers will be intrigued by the signs in the parking lot, drawn into the museum out of curiosity, and engaged by the visual and auditory experiences that are available to them inside. Recently, Spencer Director Saralyn Reece Hardy discussed the project with Davidson-Hues and Velasco. An excerpt of their conversation follows.

Saralyn Reece Hardy: Can you talk a little about what it’s like to collaborate with the Spencer, and also to collaborate with each other?

Maria Velasco: Collaborating with the Spencer is such a joy, because you have a fabulous team. Everybody’s very inspired and inspiring, and you really make it easy for artists to go to work with the museum because you open the doors and the resources and the facilities. And I find that to be not necessarily the norm in every occasion when artists are invited to do exhibitions. I very much like participating in collaborations, and Janet and I have a history of collaborating, so I know that we are going to come up with ideas that are challenging and interesting and that open doors to my own creativity.

Saralyn Reece Hardy: Maybe you can share what some of those collaborations have been like, what some of those ideas are?

Janet Davidson-Hues: Maybe you know or maybe you don’t know, but it’s not always easy collaborating with another artist. But Maria and I have done some things together in the past, and we have such a nice working relationship between the two of us. Even though we have different aesthetics, there are a number of things that are similar enough that we can work well together. We each have our strengths and weaknesses, and we play to our strengths—in other words, maybe Maria is better at doing one thing than I am, or I’m better at something else, so we really dovetail our strengths. Plus, we really enjoy working together. I think we have trust in each other, and we know that everything will work out evenly in the end. So it’s been really a pleasure for me. We do have a number of the same interests. We’ve done a number of performances together; that’s really where we started collaborating. We have an interest in space and the activation of space. Sometimes that involves the performative act—not necessarily performance art, but the performative act of making the art, which in many ways is what Stop Look Listen seems to be, just by the labor we’re engaged in…. And another thing about this is the community dimension. It’s sort of spiraled out. We’ve ended up working with people all over campus—the parking department, the police department, the sign shop—so it’s been really interesting from that aspect. The interest and support that has been shown from everybody with whom we’ve had contact at the Spencer and the other departments has been terrific.

SRH: The kind of work that you two are doing is very community-involved. You need people to actually do it. You need the audience to be actively helping in the production. So what do you think it is about projects like this that are so appealing to people? What triggers this kind of interest?

MV: I think people feel honored to part of something that is creative and a little different, something that takes them out of their typical routine. I think the general perception of art and artists is that it is something unreachable. When people get an opportunity to interact and work with a real artist and they see that this is a normal person, they get excited to be a part of that. I have experienced that a lot. For me one of the biggest pleasures is to see a carpenter who helped me build a shelf come to see the show, something like that. Art is something that touches people, a gift that you always hope can transform the lives of those who experience it. If I experience that transformation in myself, then I also know that it has the potential to transform others, or at least invite transformation.

JDH: I would add that I think the process of putting all this together from the very beginning, working with and including a lot of different people in the process is what’s so appealing to people who are not normally involved in making art or working in the museum. So the process of creating this project is important not only to Maria and me and to the museum, it’s also part of why people on the outside are interested in becoming involved.

SRH: Janet, you mentioned the concept of activating space, and I’m curious about that because the two of you thought a lot about how you would enter into this space. How is activating the space at the Spencer unique? What are the characteristics you considered?

JDH: For me, there are multiple parts of this project that are different but yet linked together. From the creation of these signs, which will start outside, the idea from the beginning was to provide a unique experience for the viewer. Then we asked how we could do that. I don’t even remember how we got started in the parking lot, but we ended up thinking about signage. From there we came up with doing signs that started outside the museum rather than inside, which would be much more predictable. We thought we would activate the space outside the museum first, in kind of a subtle, humorous way, because I think often times if you can get people to laugh and smile a little bit initially, then they’re more receptive to something else that you might want to have them experience. Then the idea of using sound, that’s another way of activating the space inside one’s head, as well as the actual space surrounding the pieces. And the idea of having an irreverent audio tour instead of the standard issue that is instructive and which is excellent, I liked the idea of challenging the viewer and making them part of the whole process by asking questions, by giving them some sort of nontraditional view, and maybe not being so instructive. I don’t know. We know pretty much what we’re doing as far as the audio, but it’s not finalized.

MV: For me, the audio will add another layer that is more experiential. For example, for the Standing Amida Buddha, I am very interested in doing a simple reading of a meditation by a Buddhist monk, Thich Nhat Hanh, who is one of the leaders of the engaged Buddhism movement. So you will be sitting in front the piece maybe expecting something historical, but you’ll get this meditation instead.

JDH: And there’s already a lot of valuable information listed out there about what period it is and where it’s from, so we’re probably not going to give that on the audio tour.

MV: We also think it’s very important to make the work current, to make it contemporary and relevant to their lives.

SRH: And of course that’s one of the ongoing challenges of dealing with historical material and existing in the university world where you’re thinking about both the past and the present. So this will be an experiment in how we address those issues. I hear you talking about relevance and irreverence, which probably is catching people a little off guard. Do you think of that as part of your role as artists—to surprise?

JDH: I certainly do. I’ve always felt that way. I think the reason I feel that way is that as a spectator, as someone who likes to view art as well as make it, I love it when an artist makes me stop and think about something or question something or do something I wouldn’t normally do. If I can translate that into my work as an artist, from the viewpoint of a spectator, that’s very important.

SRH: You use the title Stop Look Listen. I’d like you to talk about that a little, because as I think about that title, if there were instructions about what to do in life generally when you wanted to emerge from your numbness, or have a little breakthrough in your day, it requires a certain kind of attention. And I am wondering what was in your minds as you settled on that title.

JDH: I think our original title was Point of Departure, or something like that. Then out of the blue, pow, it just kind of hit me that the grandest, most literal cliché that we could use that just summed up this project perfectly was Stop Look Listen. And it’s so familiar to people because it is a cliché, but when you really examine it, it’s like you say, a lesson of life, a rule to live be regardless of what you’re doing. So it just seemed to work, particularly once we got so far as deciding to work outside, having people drive their cars up and stop, notice these signs and look, and they’re hopefully drawn into the museum because of these fabulous, funny signs they see in the parking lot. Then they’ll be given headsets and they can listen. So it just seemed perfect.

SRH: And I love the continuity of the vocabulary of the signs and the vocabulary of the title, because you’ve got it all wrapped up in a very tight concept that is manageable. But you’ve made a fairly bold statement both about art and about signage. I don’t know that we can even fully describe that, but part of what I see in it is the message that art is for everyone. The signage is out in the public, and just because it happens to picture a rare and valuable object, it’s very important that it be available to all people. And that’s the role of a museum—sharing our treasures with the public. So I love the fact that you’ve democratized these works of art and invited us in.

MV: When I think about the structure of the piece, I like very much the way it is accessible and integrated with the experience outside of the box. I can see it growing, and that would be very exciting. I see it also as a treasure hunt. I mean, as much it’s very bold and obvious on one level, on another level it has a very alluring treasure-hunt aspect in which I’m also very interested. Probably we won’t witness that, but we hope that people are going to be pulled by an invisible thread, that they’re going to want to move around the galleries and look for certain works and want to figure out which piece is what. I think it’s very…sexy.

JDH: Because on the audio tour we are overlapping some of the pieces that we used for the signs but not all of them. There are three pieces that are on the signs that we’re also going to include in the audio tour, and then we have several other audio-tour pieces that are not signs. So there’s a little bit of overlap, but we didn’t want to just have the audio tour with the same objects that we chose for the signs.

SRH: Obviously there are objects of great importance in the museum, but there’s also this desire I think for audiences to be more involved in process, which has to do with the question, “What does the art museum have to do with my life?” In the course of the project, what were the key questions you posed to yourselves in relationship to what it had to do with people’s lives?

JDH: Hopefully it will enrich their lives by making them think and learn something not only about the objects but about themselves. How they respond to some of these things—maybe some people will even be offended, but at least they’ll think about it.

SRH: Offended by the oversimplification of the works, or the fact that it looks somewhat like universal signage?

JDH: Well that was the intention. That was part of the idea. They’re actually made of the same material and made at the same place on campus that makes the traffic signs. But they’re not traffic signs. So I love that paradox, that they seem to be one thing but they’re really not but then they really are. So there’s that constant sort of question about “What is it?” Which of course that goes back to “Is it art?” And that’s what I hope people will gain from it: a certain enrichment to their own lives as well as learning something about the collection at the Spencer.

SRH: How did you arrive at the specific works of art that will be featured on the audio tour or on the signage?

MV: We were looking for images that could be translated in iconic ways and that would result in interesting signs. We were also interested in choosing images that would be as inclusive as possible.

SRH: So you wanted people to be walking throughout the museum?

JDH: We probably would have preferred to do 20 signs, 20 different pieces from the collection, and we probably would have preferred to do 25 different audio clips. But we were limited by budget in what we could do. So since we’re only doing seven images on the signs, we had to be even more selective. But we did try to do somewhat of a cross-representation.

SRH: Well it is our hope that we will annually have some sort of modest artist’s project going on in the museum because it does help us shift our thinking. One thing I’m struck about having this project start in the parking lot is the anticipation that these signs will create. Not only the curiosity, but the anticipation factor. You alluded at some reflection inside someone’s head, listening, and I’m wondering if you as artists are thinking consciously about the continuum of anticipation to see, seeing, then reflecting upon seeing? Do you have that continuum in your head?

MV: When I look at something it reverberates and I enjoy that very provocative and personal experience when you come upon a smell or a color or just an appreciation of something that your looking at, and you consider how that relates to something you have either seen, experienced or heard.

JDH: Like Maria mentioned earlier about the layering of all our senses, including sound as one of the ones that we are promoting in this project helps multiply the experience. If there were no sound, it would still be a good experience, but having something extra — a voice or a sound that is either appropriate or inappropriate— I think just adds a freshness to the experience.

MV: We haven’t really sat down to analyze it, but I think we see it as a holistic experience, where art has an ability to be an ideal place for integrating parts of the self, parts of the culture that you don’t understand or maybe don’t even want to hear about. Art can do that.

JDH: And I think we’re working on this fairly intuitively rather than analyzing it and saying that this will work because of this or that intellectual reason. It’s just kind of what feels right. That’s just the way I work, and Maria works the same way.

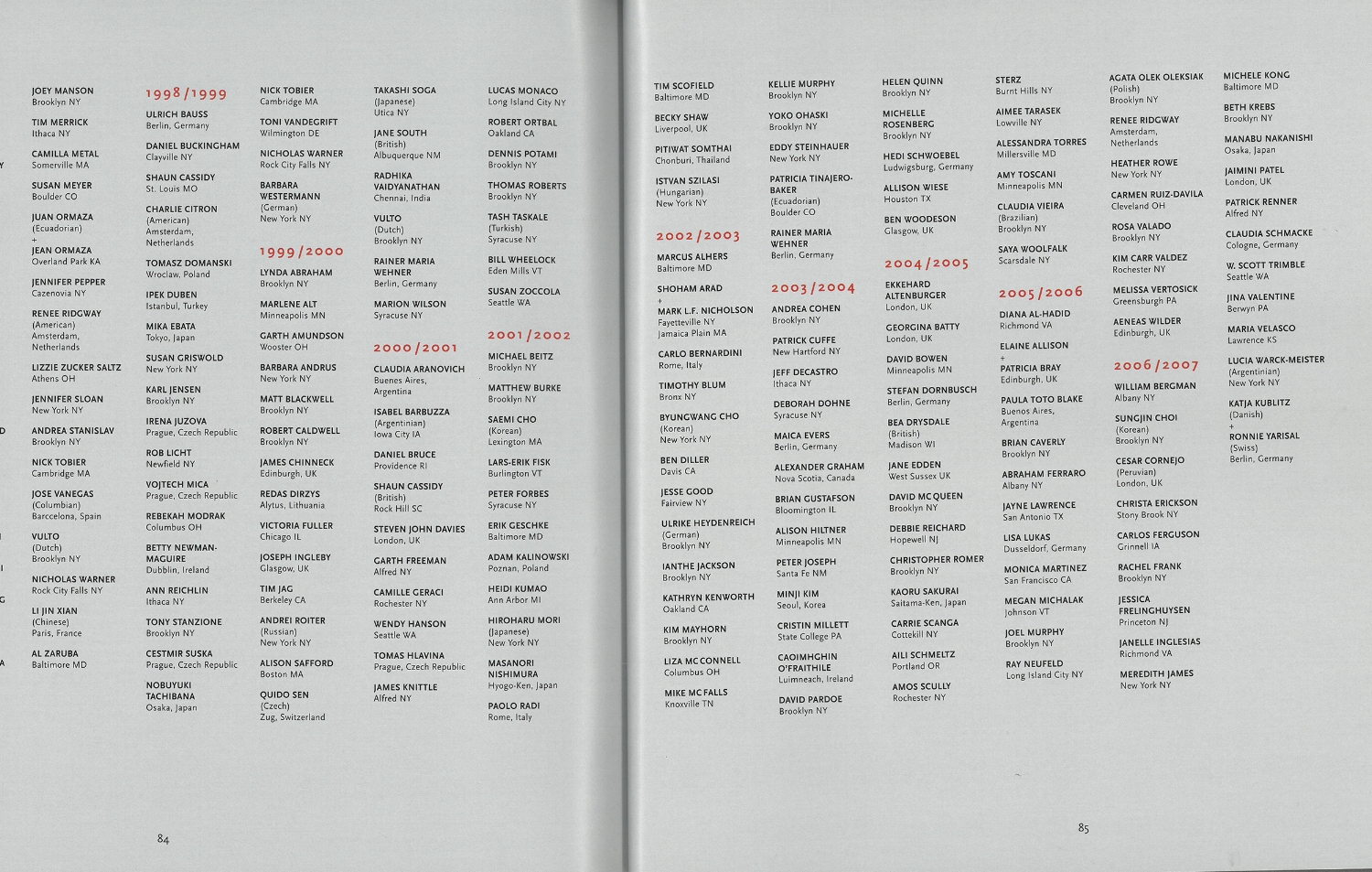

2007

"Sculpture Space [the book]", Catalogue, edited by Lin Smith Vincent with Sydney L. Waller, Sculpture Space Inc., Utica, New York 2007: p. 85

[...] Sculpture Space [the book] narrates the compelling story of the 30-year-old international artists’ residency program. The book documents the eventful history and ever-changing cutting-edge contemporary art created at our non-profit studio workspace. Dozens of the artists who attended Sculpture Space are featured in the book, which includes an extensive master list of professional artists who since 1976 have enjoyed residencies in the former Utica Steam Engine & Boiler Works plant. Sculpture Space has provided residencies to upwards of 400 professional artists from around the world since its founding [...]. Read the full article here.

2007

"Material Matters", Exhibition Postcard, The Albrecht-Kemper Museum of Art, Saint Joseph, MO

2005

"Vogelfrei 6 Zehn Jahre Kunstentdeckungen In Privatgarten", Sechste Kunstaktion Im Darmstadter Komponist envier tel Und Auf Der Schlossbastion, September 3-25, 2005: p. 56 (photo)

Ute Ritschel, independent Curator.

2005

“Women Beyond Borders. The Art of Building Community”, Exhibition Catalogue, edited by Cynthia Anderson, Carey Hobart, and Julie Simpson, Women Beyond Borders, California 2005: p. 75 (photo); pp. 8, 87

"WBB was a timely endeavor documenting women's visions and connecting them at the end of a century which had seen their struggle for rights and freedoms. It was one of our most popular shows and meaningful exhibitions and surpassed all of our expectations!"

Nancy Doll, Curator and Director, former Contemporary Arts Forum, Santa Barbara, CA.

"The most far-reaching exhibition of the year was Women Beyond Borders, a reaffirmation that good things come in small packages. Small wooden boxes which were sent to women around the world came back as works of art, filled with meanings from politics to motherhood to feminism to pure art.

Joan Crowder – Santa Barbara News Press, 1995.

"Gratitude is extended to the many venues and participants around the world-including artists, curators, board members, friends, and patrons--who assisted in making the concept of Women Beyond Borders a reality:

"To Lynn Redgrave, for graciously representing the project as honorary Chair. I am particularly indebted to the core group of artist collaborators: Elena Siff (cofounder), Elisse Pogovsky-Harris, Victoria Vesna, Beverly Decker, Evelyn Jacob, Anna Jud-Hallauer, Alice Hutchins, Saritha Margon, Isabel Barbuzza, M. Helsenrott Hochhauser, Ciel Bergman, Mary Heebner, Judy Weisbart, Sky Bergman, Rose Bilat, Joan Tanner, María Velasco, Penny Paine, Jana Zimmer, and Seyburn Zorthian [...]"

Lorraine Serena, Founder and Artistic Director.

2002

“Mostly Square”, Exhibition Catalogue, School of the Arts, University of Kansas, 2002: (photo)

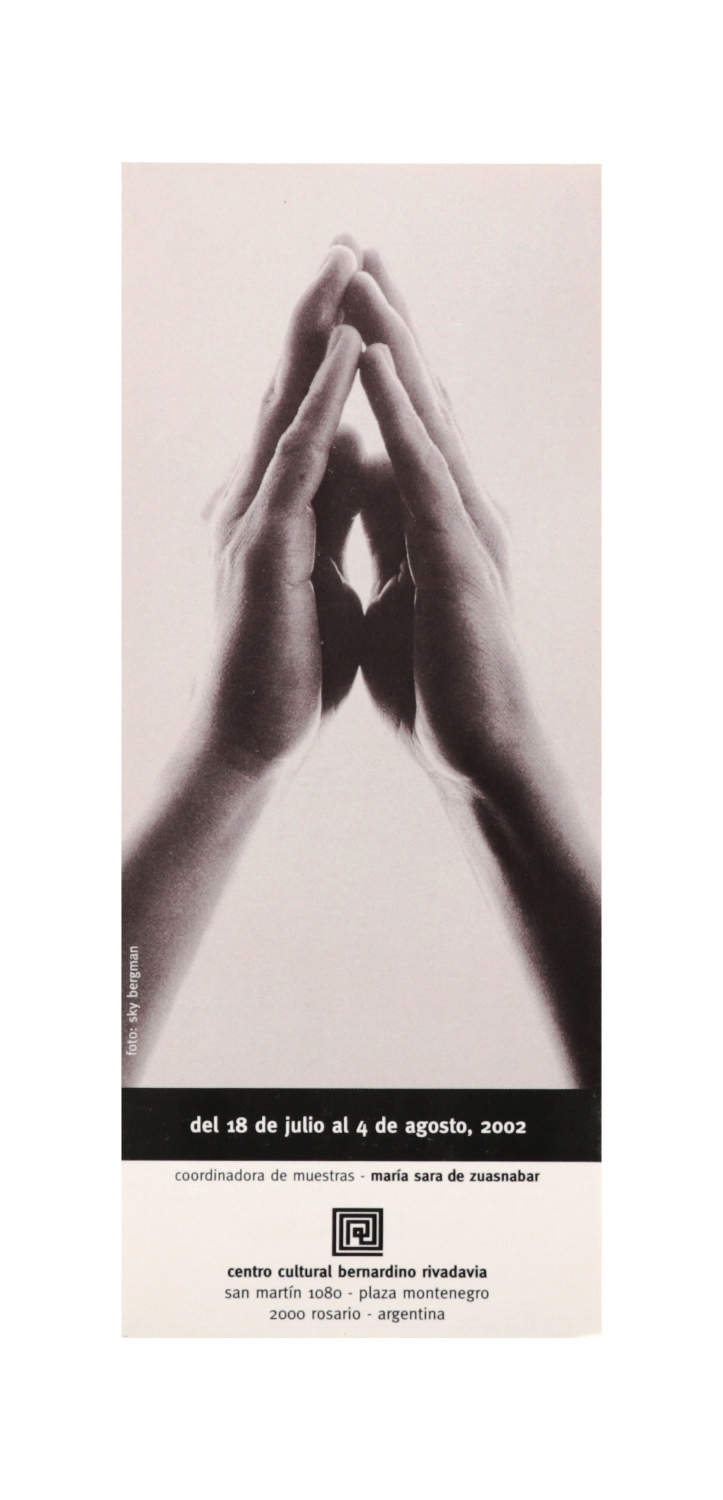

2002

“Los Labios de Teresa”, Exhibition Brochure, Centro Cultural Bernardino Rivadavia, July-August, 2002: (photo)

2002

Escobar, Ticio. “La Conjura del Silencio. Cómo Inquietar Mediante la Belleza a un Público Habituado al Ingenioso Esteticismo de la Publicidad y el Diseño?”, Ultima Hora, January 5-6, 2002: Correo Semanal, Creación. La Resistencia del Arte en los Tiempos del Mercado, front cover (photo) and pp. 12-13 (photo)

Artwork (clockwise from top left): Osvaldo Salerno, "El Sigilo", fragmento de una instalación; María Velasco, "Mea Culpa", 1997, Mezcla de escultura/instalación; Gustavo Benitez, "Sintaxis", elementos de una escritura mínima, objeto; Nelson Ramos, "Silencio, Instalación, 2001; Patricia Israel, "El Deseo de Antígona", Pintura.

La Conjura del Silencio

Este artículo se refiere a las posibilidades transgresoras que ofrece el arte contemporáneo en el centro de una escena dominada por la hegemonía globalizada. Cómo inquietar mediante la belleza a un público habituado al ingenioso esteticismo de la publicidad y el diseño? Cómo trazar una nueva señal en un espacio público repleto de marcas, de logos, de anuncios, de imágenes? Cómo escribir un no sobre la vitrina que exhibe la disidencia como un artículo exitoso de moda? Cómo representar la complejidad de la diferencia en los tiempos de Discovery Channel? O, bien, cómo asombrar en medio de una explosión espectacular de recursos mediáticos, de un desaforado mega-show pirotécnico de prodigiosas escenografías virtuales? (Cómo conmover a un público que ve una hecatombe real por televisión y por este medio asiste diariamente a su desarrollo genocida?).

Sin descontar que el arte actual dispone de otros recursos contrahegemónicos, a continuación se exponen dos expedientes suyos dirigidos a desorientar los rumbos de la significación establecida para destrabar sus contornos cerrados. La primera tendencia, afirmada ya a mediados de los años 80, reacciona tanto en contra del espíritu light y los clisés de la publicidad como en oposición a los discursos lánguidos de un modelo político formateado en clave de mercado: en contra del discreto encanto de la forma concertada. Y lo hace en una escena amenazada por la virtualización de lo real nombrado, por la disipación de sus densidades y la mass-mediatización de sus conflictos y sus ganas. Por eso reemergen los temas densos, las denuncias olvidadas, como la injusticia social, la devastación ambiental, y la frivolidad programática sostenida por la alianza política-cultura-tecnología-mercado. Y, buscando remover las costras almacenadas por los estándares de la cultura globalizada, irrumpe un dramatismo visceral y orgánico, violento las más de las veces, crudo en sus decires apurados. Un pos-realismo, por llamarlo de alguna manera, que trata de tocar lo real directa y ferozmente, abriéndose paso por entre los estratos de significaciones sobrepuestas como si quisiera constatar su existencia amenazada.

La segunda tendencia, consolidada a partir de los 90, también se afirma de cara a un tiempo atiborrado de imágenes. Una historia durante la cual las cosas aparecen interceptadas por una maravilla de signos que las nombran desde mil lados (lo real "babelizado" y sobreescrito, reetiquetado, ilegible). Pero esta segunda estrategia se plantea desde el otro extremo: cuestiona la superficial estridencia del mercado, replegándose, hosca, sobre sí, bajando la voz, trabajando el filo más vibrante del silencio: las entrelíneas de un lenguaje saturado, el detrás o el después de la algarabía que levanta la publicidad triunfante. Esta tendencia se acerca al minimalismo en lo escueto de sus signos depurados, pero no busca como aquél purgar el lenguaje hasta sus elementos básicos sino hacer un alto y callar, para dejar que se escuchen otros rumores, otras voces, alguna verdad que avanza sutilmente y a contramano.

Quizás ambas tendencias resulten la cara y contracara de un único gesto que no acepta la transformación del acontecimiento en bullicioso espectáculo. Estamos cerca de Vattimo, cuando afirma que, en contra de la estetización masificada, el arte termina a veces renegando de todo elemento de deleite inmediato en la obra --el aspecto "gastronómico"-- al sumirse en el puro y simple silencio. Siguiendo a Adorno, dice que "en el mundo del consenso manipulado, el arte auténtico sólo habla callando ..." Pero cómo puede hablarse callando? Puede hacerse mediante la poesía, esa contra-dicción que busca perturbar el lenguaje para forzarlo a desandar su curso programado.

Lo poético dice mucho más por lo que omite que por lo que declara: habla desde la falta. Por eso, cuando nombramos hoy el sinsentido del arte, no estamos proclamando el vacío de sentido sino proponiendo marchar a contramano del sentido único. Desde sus tropos y sus omisiones, y a través de sus signos desviados, los artistas sí pueden disputar un lugar al mercado, entidad antipoética por definición y preferencia.

Por eso, cierto arte actual --sobrio y frugal, reducido en su espesor sensible, escueto en sus formas mínimas-- busca resistir replegándose en los terrenos severos del concepto. Ahora bien, el mercado no entenderá de poesía pero bien conoce las reglas del pensamiemo calculado. Entonces, el concepto, que anima gran parte de los planteamientos actuales, también debe ser turbado por la poesía si pretende ser más que concepto satisfecho y concertado.

Así como debe serlo el silencio si quiere ser más que ruido vaciado (puede callar el arte pero no enmudecer). Desde sus rodeos y sus ambages, desde sus silencios trepidantes, el lenguaje descarriado puede signifiar un gesto más subversivo que la denuncia más drástica. Y puede hacer entrever, fugazmente, otro lugar desde donde anticipar futuros deseables y, en pos de ellos, renovar las ganas.

Ticio Escobar, Art Critic and Director, Centro de Artes Visuales / Museo del Barro, Asunción, Paraguay.

2001

“Esperando a Goya. Muestra de Arte Español”, Exhibition Brochure, essay by Ticio Escobar, Art Critic and Director, Centro de Artes Visuales/Museo del Barro, October-November 2001: (photo)

Presagios

Esta muestra reune un grupo significativo de arte espafiol de cara a un horizonte común imaginado por la curadoría en torno a dos ejes. El primero de ellos busca reunir un conjunto de obras que, en pos de errancias o azares, contingencias varias y casualidades recalaron en el Paraguay y acá quedaron como hitos dispersos de un camino posible. Este es el rumbo que quiere reconstruir la muestra trazando un contorno entre piezas dispersas, desvinculadas entre sí en su destino y en su origen, entre sí desconocidas.

Nadie habia pretendido reunirlas en una muestra o una sola colección de arte español; ahora las reune el designio de esta muestra que trata de buscar los vínculos que todas las obras guardan, cómplices, entre sí. Pero las piezas que integran este lote no solo difieren en sus procedencias y sus destinos, también lo hacen en sus estilos y en sus tiempos: la muestra confronta pinturas del S.XVII ( Bartolomé Esteban Murillo) y fines del S.XIX y comienzos del XX (Santiago Rusiñol) con propuestas contemporáneas (María Velasco, Pablo Márquez); imágenes del geometrismo español de los años 70 (Jose María Iglesias) con la figuración expresionista y politizada de la misma década (Rafael Canogar).

Confrontadas entre sí, encaradas unas con otras, entroncadas en una disposición común y un espacio compartido muestran el las el nexo de un secreto que una a una quiza no permita entrever: casi todas las obras estan pregnadas de cierta pesadumbre que oscurece algun borde o un costado de la sensibilidad española: quizá el vago temor que levanta la soledad o el remordimiento, la culpa o el deseo, quizá la memoria antigua de la muerte o la zozobra ante lo desconocido o lo irracional, el limite de la razón o el otro lado de su frontera: la inquietante sensación de una espera, tal vez.

Desde ese mismo pesar guardado y compartido, todas estas obras estan convocadas alrededor de una espera imaginaria. Están allí colocadas, expectantes, demorando en parte su estar, anunciando una obra que a todas alimenta. En torno al segundo eje de esta muestra se expone obra gráfica de artistas españoles contemporáneos. Detentan ellos nombres sonoros: Picasso, Dalí y Tapies, Chillida, Manesi y Gordillo, Clavé, Saura. Nombres-hitos, nombres que también nombran a Goya. Y se nutren de su gráfica, comprendida como afán moderno y gesto visionario. Como presagio o cifra de aquel momento sombrío que acecha desde el otro lado, desde el detrás de la razón o el fondo del sueño desvelado. Develado. Todos ellos revelan desde la vigilia de una conciencia contrariada. Todos esperan a Goya desde el desvarío y el exceso, desde la clara forma heredada de Velázquez, desde el gesto doloroso y retorcido que legara El Greco, desde el romanticismo que espera en Los Desastres de la Guerra, el surrealismo cobijado en Los Caprichos o Los Disparates, el expresionismo oscuro encerrado en la Quinta del Sordo, el impresionismo anunciado en tanta pincelada, en tanto color que tiembla y se retrae. Que espera convertirse en mancha gráfica, en línea escueta, en escritura trastornada.

Tico Escobar, Octubre 2001

Con la presentación de esta muestra, el Centro de Artes Visuales/Museo del Barro quiere sumarse a las celebraciones de los 25 años de trabajo cultural llevado a cabo por la Embajada de Espana en el Paraguay a través del Centro Cultural Juan de Salazar. Este Centro ha marcado fuertemente el devenir de nuestra cultura a lo largo de esos 25 años. Durante el tiempo largo de la dictadura del General Stroessner, ha servido de cobijo solidario a los trabajadores de la cultura y ha constituido un espacio de creación, encuentro y difusión resguardado de la censura y protegido del miedo.

Durante la época de la transición, el Centro sigue afianzando sus espacios, físicos y culturales, y acompañando el devenir difícil de las artes y el pensamiento. Es justo reconocer que, como pocos países, España ha apoyado el desarrollo de nuestra cultura y ha apostado a su devenir y compartido sus afanes. Pero también es justo reconocer que no basta sóIo una política de Estado, por más favorable que fuere -como lo es en este caso- al crecimiento de la cultura. En abstracto, ese interés no hubiere dado los frutos que dió si no hubiere recibido el impulso diario y efectivo de nombres como los de Paco Corral, Lilo Aceval y, hoy, Nilo Fernández. Esta mención también es necesaria.

Por eso, esta muestra se suma con ganas a las celebraciones de 25 años de trabajo. La exposición, "Esperando a Goya", reúne un conjunto de obras que, realizadas por artistas españoles, se encuentran en el Paraguay. Como se encuentra en el Paraguay mucha obra y mucho hacer beneficioso de españoles que han pasado por acá, o acá viven, o han enviado sus obras o estas han sido adquiridas. El Museo quiere ahora imaginar un itinerario posible entre ellas, y, al hacerlo, anunciar la muestra de Goya que culminará este ciclo y cerrará las exposiciones que vienen recorriendo otras ciudades del Paraguay y dejando a su paso señas e imágenes.

Curated by Osvaldo Salerno, Artist and Director, Museo del Barro, Asunción, Paraguay.

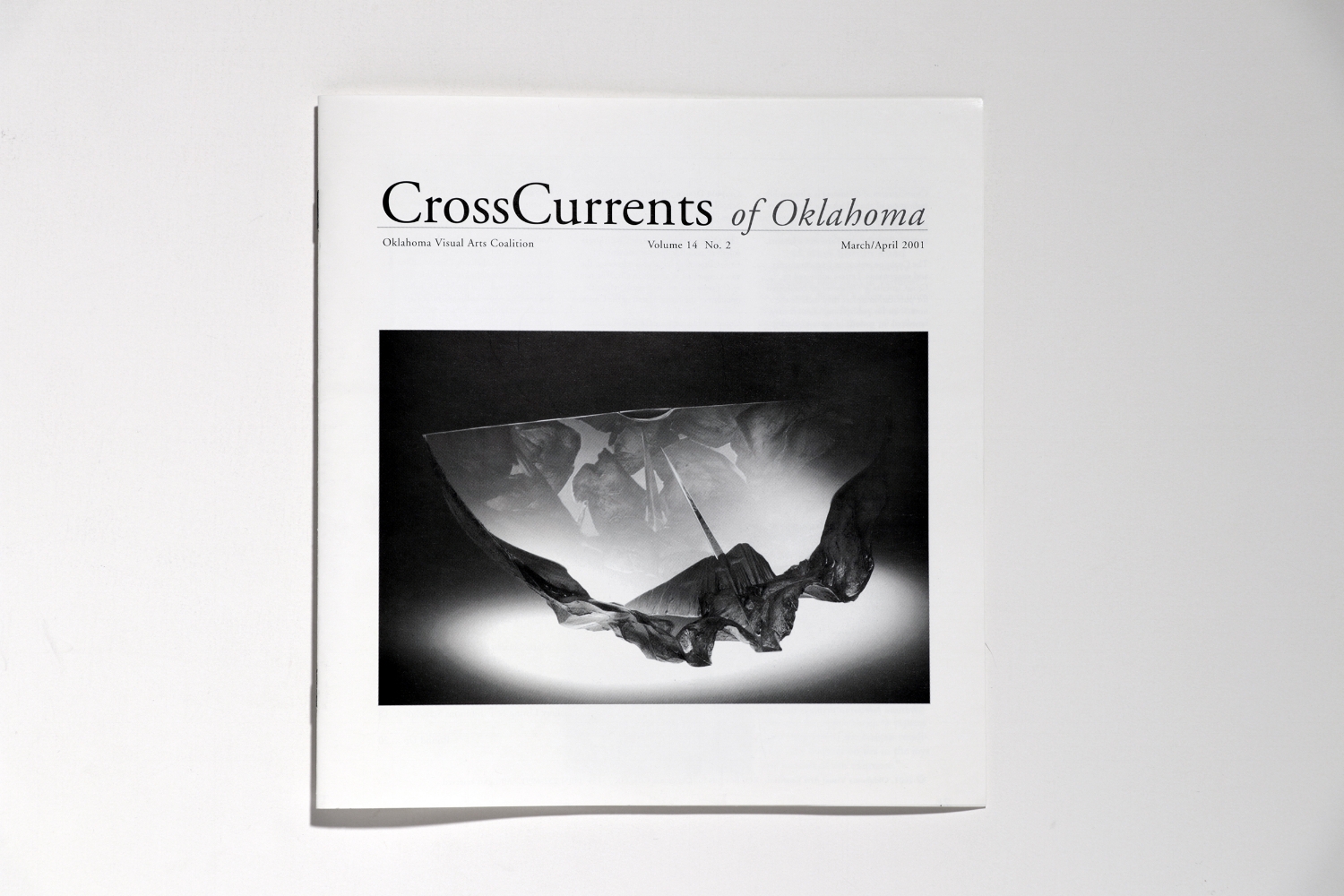

2001

Duncan, Ronald J. “María Velasco And ‘Tierra De Nadie’ “Cross Currents of Oklahoma, Oklahoma Visual Arts Coalition, Vol. 14, No. 2 March/April, 2001: pp. 13-15 (photo)

Maria Velasco and Tierra de Nadie

In Maria Velasco's exhibition or installation works at the Individual Artists of Oklahoma gallery (in September of 2000), the Spanish artist made powerful visual statements about the use of women's bodies, ranging from celebration and sacrifice to purification and veiling, Velasco's pieces are conceptually complex with layers of meaning that cannot be easily deciphered by a casual observation. Her written statements that accompany the pieces are road maps to her thoughts and guide the viewer to understand her own process in developing the pieces. Her art, based upon research, evaluates the human condition and confronts the hidden assumptions of the role or women, relationships and society.

The centerpiece or the exhibition was “Tierra de Nadie" ("No One's Land): a large altar-like piece laid out in a cruciform. The central axis of the piece is a long table covered in white satin. White dinner plates are placed on the table, and the center or each plate has a close-up photograph of a part of the artist's body beginning with her face and ending with her feet. The plates are laid out seemingly as an invitation to dinner, but they are empty except for the suggestion or the artist's body. Cutting across the table at mid-point is a wall of human hair several feet wide and probably eight feet high. This wall of hair simultaneously attracts and repels. The field or brown and black hair is warm, but the contrasting whiteness of the satin and dinner plates suggests coldness, or is it purity?

Velasco said that "when he makes an installation piece, she likes to make it fit the physical space where it will be located. When she first made this piece in Paraguay, ''This space they gave me had a waII in the middie of it…, and I wanted to find a way to eliminate that wall or give it a role... It gained entity at the end because it became a part of my body. It represented something that was a body part instead of the wall." That wall became an essential part of the piece. It is the wall that divides the Spanish and the Guarani and also men and women. Although the wall of hair is about division, paradoxically it also unites the two opposite parties, whether it be in the passion of antagonism or the search for peaceful co-existence.

This enigma or opposites begins to reveal itself in the artist's statement about the piece which was stimulated by both experiences in Paraguay between the Spanish and the Guarani Indians during the Conquest in the 1500's as well as by Velasco's own mission of discovery to Paraguay. She later said, "When I arrived there (i.e. in Paraguay) ... I was already fantasizing about the moment when two cultures look at each other, and the fears that may happen when people see someone who looks so different." The stories that she heard in Paraguay about the contact between Spanish and Guarani became the conceptual building blocks for this installation.

The Guarani and the Spanish cultures encountered each other through soldiers, and the Guarani found that one way of communicating with the Spanish men was by giving them their sisters. As the people of two cultures reached out to each other, the bodies of women became the currency of contact. That was the main idea that Velasco came to explore in "Tierra de Nadie".

"Some of the stories tell that Indian (women) were attracted to the Spaniards because they had hair. How interesting ... to be wanting to touch a body that has hair. What a funny feeling it is to someone who is not used to finding hair on the body," Velasco said.

She also found inspiration in the embroidery of Paraguay: "The indigenous people make a very fine embroidery that is made of thin, thin thread. It was passed on by the Spanish, but the Indian women learned it, and they made pieces for the missions for religious occasions ....The name of the embroidery means 'spider web' because it is so thin. There is a story about a woman whose son was attracted to an Indian woman .... Every day he tried something (to get the woman's favor), but every day he would come back depressed to the house because it did not work ... His mother saw this, and she stayed up all night one night embroidering with the white hairs from her head. That was the first example of this embroidery. The mother gave it to the son so that he would give it as a present to his desired love, and it worked, and they fell in love."

"So, I started thinking about these connections between body, magic, and self, and the rites of passage. Giving the body is the ultimate gift that you can give to someone. In myriad ways all of these stories are in the piece ("Tierra de Nadie"), but there is no way to pull them apart. That is when I started thinking about the hair, that is something that is given, something that is beautiful .... In hair we have the qualities of body and death joined together...." Velasco went to hair salons around Asunción, the capital of Paraguay, collecting the hair that had been cut to put on the wall. That hair represents the lives of Paraguayans today who are the descendants of the encounter between Spaniards and Guarani.

In addition to the wall of hair, the other central element in "Tierra de Nadie" is the dinner-like offering of the woman's body in the photographs printed onto the plates. About this Velasco said, "You know there is cannibalism in many South American tribes in history. Not cannibalism, but anthropophagy, the difference being not just for defending their group but for spiritual reasons .... So, I started thinking about this issue ... eating the body with the idea that it is transformed, and that it lives through you, and that there is continuity. It is not termination, it is just the opposite, continuity. Then, in Catholicism the body of Christ is the same, but metaphorical ... so I started thinking about layering for the idea of the body on the plates .... The way we would eat something today ... the plate would be full of food, and then at the end you would find the imprint of a body (i.e., the photographs of her body on the plate) ...."

"The other story that was very crucial when I was doing this research ... the director of the Indigenous Museum ... said, 'There is this word in Guarani ... that means both to make love and to eat.' And I was thinking, how can you possibly know whether you are saying I want to make love or I want to eat? So, sexuality is again ingesting or possessing or imagining that you posses .... So, that was part of my thinking in this piece, the idea that the woman is being offered .... Who is the winner when you have a relationship with someone ... ? That is the title of the piece 'Tierra de Nadie' (i.e., 'No One's Land'), meaning that you might think that you own someone but you never do." With all these stories in mind ... I decided on the fabric, the satin, to represent a woman who was given as a present in that culture. But in our culture too ... the pressure of getting married in many families, especially if you are a woman ... (is like being given in marriage). 'When are you going to have kids?' The pressure is there. The satin is representing that you are giving your body to somebody else, and that somebody else might be a person or a situation."

The plates on the white satin reflect the sacrifice of the woman, the satin almost like sheets. Velasco emphasizes the sexual implications of this sacrifice in the wall of hair rising from pubic area of the body. She said, "Then you encounter this wall of hair that you do not know what to make of. It is attractive, but it is repulsive too. You want to come close to look at it, but it is not some1hing that you expected. It represents fears and sexuality, and our not knowing exactly where we are going with things."

This is the biology of art. During the 1980's and 90's Andres Serrano used body fluids as art materials, and later Damien Hirst used the bodies of animals, and Chris Ofili used feces. As the cultural and scientific hegemony of humanity is challenged by our own social mistakes and the deadly viruses we cannot control, artists have been plumbing biology to find what meanings to life lie within. The use of human hair as cultural history in Velasco's work is an extension of this search for art material and comment in the biology of the species.

María Velasco makes a strong statement about the position of women in society in "Tierra de Nadie", but she also explores the use of materials and creates visual ambiguities that enrich the esthetic appeal of the piece. Elements of Christianity, ethnicity, power and gender infuse this cerebal and nuanced work, and it forces us to think about our concepts of art and the treatment of women. The casual observer will miss the multi-layered complexity of Velasco's work, but the person who looks at it in depth will find a uniquely rewarding experience of art and intellectual challenge.

Ronald J. Duncan, Professor of Anthropology and Museum Management, Oklahoma Baptist University, Shawnee, OK.

2000

Lieberman, Claire. “That Food Thing You Do”, Sculpture Magazine, December 2000: p. 50 (photo). Download the article on pdf here.

That Food Thing You Do

[...] In Remember Lot's Wife..., María Velasco also uses the symbolism of salt to explore the role of women in society. She comments: "Salt was once a mark of richness and also a sign of decay and death...The story of Lot's wife is used as an example of bad behavior by women. " In her installation at the Salina Art Center (1997), a huge pile of salt presses against the interior side of a glass wall, visible from a well-trafficked street. An oversized transparent photo of a woman's torso and head is supported by the salt, seemingly compressed into the glass. Velasco writes: "Here, salt is used as a reference to the geological past of Salina, and because of its contradictory qualities of preserving flesh, as well as destroying living matter. In this installation, salt becomes the landscape from which Lot's wife emerges in a moment of courage or against which she disappears in a moment of doubt." Velasco's undertaking raises issues of exchangeability. If food can be replaced, its transience becomes unimportant. If it is not a unique object or a one-time event, the visual object is, in effect, substitutable. Questions of permanence are obscured, and the prevalence of object over subject may be exerted. This is a significant factor in the work of Long Phaophanit and Felix Gonzalez-Torres. [...]

Claire Lieberman, Artist and Independent Writer.

2000

"Art In Kansas City", Art In America, August 2000: p. 22 (photo)

1999

"Estampa 1999. Salón Tentaciones. VII International Printmaking Art Fair", Exhibition Catalogue, Fundación Actilibre, November 5-9, 1999: pp. 40-41 (photo)

Víctor del Campo, Curator and Director, Feria de la Edición y el Grabado, CEO, Gabinete Art Fair, Spain.

1999

"Tentaciones", Guía del Ocio-Especial Estampa 99, October 29-November 4, 1999, p. 8 (photo)

1999

"Body", Exhibition Catalogue, essay by Saralyn Reece-Hardy, Director, Salina Art Center, February 20-May 16, 1999: (photo)

Body

The body is at once fixed and fluid. As sensor and sender, home base and traveler, the body experiences and expresses our most intimate impulses and abstract concepts. Gestures and responses create the languages of the body -- the mysterious rituals and relationships that form the site of our emotions, relay station of our senses, and scribe of our consciousness. The body conveys and receives, consumes and releases. The body is both the mark of identity and the author of imagination, the first and final location of the self.

While often treated as an object. the body is more fundamentally a dynamic community, constantly exchanging inner and outer domains. Breath and fluids flow through and out into the environment, skin falls away, heat radiates, cells replenish and split, two people create another, voices carry. Biologically transient sojourners, bodies form, disperse, and transform their impressions and expressions linger.

Looking beyond the skin-thin boundary of the body, we know that deeper portraits include heart rate, chromosomes, and bone structures. Visceral understandings of bodily processes undermine the modeled bodies we learn to desire, the clinical bodies we comfortably scrutinize. Extending the boundaries of the body outward, cyber-bodies appear on screens with disembodied voices; through keys and actions we send our identities and personal marks into the broadest communities of all. At the same time, synthetic bodies, life supports, transplants, cosmetic surgery. and scientific imaging introduce questions about what is ideal, what is normal, and how we ultimately wish to construct or control our desire for health, attraction and immortality.

Several influences attracted me to the body as a curatorial project. The first was my own reliance upon the body as a dependable way of knowing the world. Somatic responses to forms, feelings and ideas led me to artists who seem to be inviting viewers to experience art with their whole bodies. The second was the plethora of important contemporary art about the body that continues to emerge. Drawing from every source imaginable, artists persist with the body as an authentic and primary place and way to pose questions. Experiencing and presenting this art for more than two decades stimulated my appetite for a longer look at the questions surrounding the body in contemporary culture. Finally, the physical, social, psychic, and sexual body often surfaces as a favorite theme of the Art Center's communities. No other topic raises so much discussion and provokes more dialogue.

This exhibition brings together artists who use the body as a physical presence and as a form of language originating in both nature and culture. Body exposes the inseparability of the material and symbolic body, and explores the physical self as a biological and imaginative site. Some of the art uses formalized gesture, pose. art historical narratives. literary sources and theory; other works employ codes. signals, and mapping more commonly found in medicine or science. Yet others demand a social reading, tapping the formulaic visual codes of popular culture portrayed in magazines. television, and through photographic manipulation.